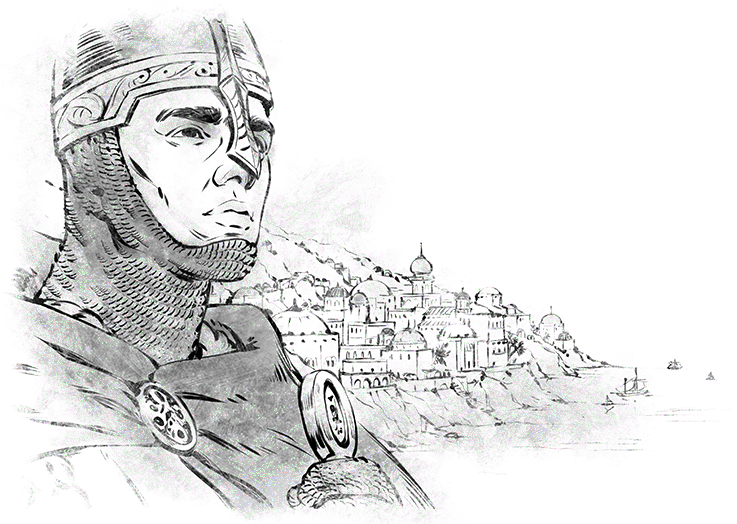

Experience the diverse cultures and martial spirit of the Mediterranean’s crossroads as you build one of the most coveted kingdoms of medieval Europe. The Sicilian unique unit is the Serjeant, a hardy infantry unit that can construct the formidable Donjon.

Experience the diverse cultures and martial spirit of the Mediterranean’s crossroads as you build one of the most coveted kingdoms of medieval Europe. The Sicilian unique unit is the Serjeant, a hardy infantry unit that can construct the formidable Donjon.

Quick Card

Infantry civilization

- Castles and Town Centers are constructed 100% faster

- Land military units receive 50% less bonus damage

- Farm upgrades provide +100% additional food

Unique Units

Sicilian unique infantry unit which can construct Donjons. |

Fortification used to train your unique unit. Unique building of the Sicilians. Units can garrison inside for protection. Archers and Villagers shoot additional projectiles. |

Unique Techs

Team Bonus

- Transport ships +5 carry capacity and +10 armor against anti-ship attacks

History

As the Western Roman Empire succumbed to internal instability and the pressure of external threats in the 5th century AD, even its core was overrun; Italy and Sicily fell successively to the Vandals and then the Ostrogoths. Shortly thereafter, Emperor Justinian (482-565) of the Byzantine Empire launched a series of campaigns, led primarily by his generals Belisarius and Narses, to reconquer the lost territory. The resulting conflict, known as the Gothic War (535-554), ended in a Byzantine victory, but irreparably devastated most of Italy.

As the Western Roman Empire succumbed to internal instability and the pressure of external threats in the 5th century AD, even its core was overrun; Italy and Sicily fell successively to the Vandals and then the Ostrogoths. Shortly thereafter, Emperor Justinian (482-565) of the Byzantine Empire launched a series of campaigns, led primarily by his generals Belisarius and Narses, to reconquer the lost territory. The resulting conflict, known as the Gothic War (535-554), ended in a Byzantine victory, but irreparably devastated most of Italy.

Shortly after Justinian’s death, the Lombards flooded into Italy, seizing most of the peninsula, although the Byzantines retained Sicily and the southern portion of Italy. These regions would remain in Byzantine hands throughout the next few centuries, but were constantly threatened by invasions and pirate raids from the south as the Islamic caliphates expanded their spheres of influence across North Africa and the Mediterranean. Full-fledged conquest occurred during the 9th century, more permanently in Sicily than in Italy. In Apulia, the Emirate of Bari was retaken by Carolingian and Byzantine forces in 871, although several bays throughout the region still bear the name Covo dei Saracini, “Cove of the Saracens”, a testament to their legacy and that of continued pirate activity.

By 965, Sicily was entirely in the hands of Islamic emirs. Economic reforms and stable, peaceful administration under Islamic rule led to a period of prosperity, but Byzantine expansionism during the early 11th century led to renewed conflict with the Lombards in Italy and the Islamic emirs in Sicily. The resulting power vacuum attracted a new invader: the Normans. Originally recruited into the region as mercenaries, these intrepid adventurers and fearsome warriors saw in Italy an opportunity to build themselves a more promising and profitable future than they might find as minor nobles or landless knights in Normandy. Two Norman families in particular, the Drengots and the Hautevilles, emigrated and established themselves in Italy over time.

One such man, Robert de Hauteville (1015-1085), known as Guiscard “the Fox” by his contemporaries, arrived in Italy at the head of a small band of followers around 1047. By 1059, he ruled much of Apulia and Calabria as duke, and shortly thereafter he and his brother Roger Bosso began their campaign to conquer Sicily. Whereas Robert was a cunning warrior, Roger was an equally shrewd statesman capable of navigating the intricate political and administrative climates with which he was faced. Soon, Roger was conquering Sicily while Guiscard saw to further campaigns against the Byzantines in Italy and Greece, seizing Bari in 1071 and, along with his wife Sikelgaita and son Bohemond of Taranto, smashing a Byzantine army near Dyrrhachium in 1081.

As droves of European knights and their retinues flooded eastwards in the wake of Pope Urban II’s call for Crusade, Bohemond and his nephew Tancred took the cross and joined the crusading force. After successfully orchestrating the capture and subsequent defense of Antioch from the Seljuk Turks, Bohemond established himself as the ruler of the city, while Tancred continued on to Jerusalem. While most Crusaders were notoriously violent and brutal, Tancred earned a reputation as a crafty yet noble warrior who strove to prevent the slaughter of innocent civilians and other non-combatants during the swift Crusader conquest of Jerusalem, Palestine, and parts of Syria.

The Italo-Normans, as the conquerors and rulers in Norman Italy and Sicily are now known, were successful on the battlefield because of their fierce disposition, vigorous military tradition, keen affinity for tactics and the use of cunning, and sheer torrid speed. In these, they most closely resembled their Viking and Frankish forebears, but as they settled in Italy and Sicily they embraced local cultural customs and norms of governance. This syncretism, combined with an increasingly tolerant treatment of local populations and religious groups, created a unique and vibrant culture and laid the foundations for a successful state. The Italo-Normans were also impressive builders: they secured their lands with formidable donjons (keeps) while constructing lavish palaces and towering cathedrals.

No ruler exemplified this complex of qualities and backgrounds better than Roger II of Sicily (1095-1154), who braved internal rebellions and external invasions to unite all of Norman Italy and Sicily under a single crown and transform his kingdom into an economic powerhouse. Through the appointments of courtiers and functionaries of diverse backgrounds and the patronage of Continental, Greek, and Arabic art and culture, Roger created a truly cosmopolitan state. His successors, however, were less competent, and their mismanagement of the kingdom allowed it to subsequently fall into German, Frankish, Spanish, and Byzantine spheres of influence, under which it swiftly declined and was eventually consumed.